Presenting a new argument for the existence of God

In the modernist era, science was often contrasted with metaphysics. Nowadays philosophers accept the inevitable: the metaphysics of science. But how does the metaphysics of science stand in relation to the metaphysics of worldviews? And how do the metaphysical views of Christians and atheists fare under the scrutiny of scientific discovery over the last two hundred years? It is a remarkable fact that the Judaeo-Christian worldview is historically much better confirmed than the atheistic one. This is, in fact, the raw nerve of atheism! This is part three of the series Science and God.

Since the time when humans first wrote things down, they had metaphysical beliefs about the world. They held views about our cosmos that go far beyond the possibilities of our five senses. As such, they believed that humans have a soul (spirit), that other spirits or gods exist in a spiritual realm beyond our material world and that there is life for humans beyond our earthly existence. In the Judaeo-Christian tradition people furthermore believe in one creator God who gave his moral law and that humans have the ability (free choice) to live in accordance with that law [1].

Since the time of the Enlightenment, many people have rejected these metaphysical views. Atheists and agnostics think that these views are the remnants of a pre-scientific worldview. They reject the idea that spirits or God exist (some developed new rationally inclined views, for example, about what the idea of “God” entails but that is beyond the scope of this essay). They believe that science and only science should guide our thinking. In this regard, they often confuse science with scientism – thinking that our human existence should be viewed only in terms of empirically demonstrated facts. As such they often do not appreciate the fact that this is also a mere metaphysical view of our human existence which makes claims that go far beyond the reach of science.

The million dollar question is: which metaphysical view is correct? Both camps argue that they are right. As such a more sensible question is: How can we determine which view is correct? The problem in this regard is that the things that Christians (and Jews, for that matter) and atheists argue about lay beyond our sensible world. Although this may seem to be a dead end, it is not. A possible solution is to consider these worldviews in their historical context as theories which have over time been confirmed or denied by scientific research.

In this essay, I cast the disagreement between Christians and atheists in terms of metaphysical worldviews which can be treated as theories and ask: which one has over the course of the last two hundred years shown itself to be correct insofar as we have been able to confirm or deny its presuppositions when measured against scientific progress? I use the work of the philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) who has contrasted these metaphysical views in the context of some of his so-called antinomies, that is, conflicts of logical possibilities. In these antinomies, opposing rational positions are effectively brought into conflict with each other. I show that although the Judaeo-Christian worldview has not originated in science, it has by far been more successful than the atheistic view.

The metaphysics of science

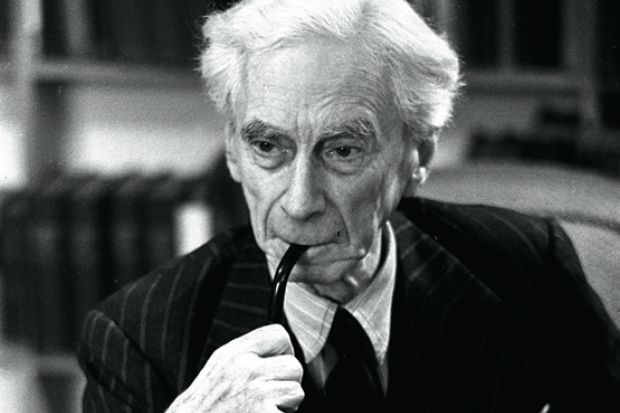

The conversation between Christians and atheists is often cast in terms of knowledge claims. In this regard atheists often present the Christian view as not built on any real knowledge. They argue that the Christian presuppositions about our cosmos go beyond that which is scientifically known and postulates things that can never be known. In this regard atheists often speak about the “god-in-the-gap” perspective: in the context of that which is unknown, one can postulate anything. The atheistic philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) famously wrote that the claims of the Christian religion are in effect unfalsifiable claims similar to saying that a tiny, undetectable teapot exists between Earth and Mars. In his view, the burden of proof lies with those making such claims to show that they are true.

In the modernist era, science was often contrasted with metaphysics. Nowadays philosophers accept the inevitable: the metaphysics of science. But how does the metaphysics of science stand in relation to the metaphysics of worldviews? And how do the metaphysical views of Christians and atheists fare under the scrutiny of scientific discovery over the last two hundred years? It is a remarkable fact that the Judaeo-Christian worldview is historically much better confirmed than the atheistic one. This is, in fact, the raw nerve of atheism! This is part three of the series Science and God.

Since the time when humans first wrote things down, they had metaphysical beliefs about the world. They held views about our cosmos that go far beyond the possibilities of our five senses. As such, they believed that humans have a soul (spirit), that other spirits or gods exist in a spiritual realm beyond our material world and that there is life for humans beyond our earthly existence. In the Judaeo-Christian tradition people furthermore believe in one creator God who gave his moral law and that humans have the ability (free choice) to live in accordance with that law [1].

Since the time of the Enlightenment, many people have rejected these metaphysical views. Atheists and agnostics think that these views are the remnants of a pre-scientific worldview. They reject the idea that spirits or God exist (some developed new rationally inclined views, for example, about what the idea of “God” entails but that is beyond the scope of this essay). They believe that science and only science should guide our thinking. In this regard, they often confuse science with scientism – thinking that our human existence should be viewed only in terms of empirically demonstrated facts. As such they often do not appreciate the fact that this is also a mere metaphysical view of our human existence which makes claims that go far beyond the reach of science.

The million dollar question is: which metaphysical view is correct? Both camps argue that they are right. As such a more sensible question is: How can we determine which view is correct? The problem in this regard is that the things that Christians (and Jews, for that matter) and atheists argue about lay beyond our sensible world. Although this may seem to be a dead end, it is not. A possible solution is to consider these worldviews in their historical context as theories which have over time been confirmed or denied by scientific research.

In this essay, I cast the disagreement between Christians and atheists in terms of metaphysical worldviews which can be treated as theories and ask: which one has over the course of the last two hundred years shown itself to be correct insofar as we have been able to confirm or deny its presuppositions when measured against scientific progress? I use the work of the philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) who has contrasted these metaphysical views in the context of some of his so-called antinomies, that is, conflicts of logical possibilities. In these antinomies, opposing rational positions are effectively brought into conflict with each other. I show that although the Judaeo-Christian worldview has not originated in science, it has by far been more successful than the atheistic view.

The metaphysics of science

The conversation between Christians and atheists is often cast in terms of knowledge claims. In this regard atheists often present the Christian view as not built on any real knowledge. They argue that the Christian presuppositions about our cosmos go beyond that which is scientifically known and postulates things that can never be known. In this regard atheists often speak about the “god-in-the-gap” perspective: in the context of that which is unknown, one can postulate anything. The atheistic philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) famously wrote that the claims of the Christian religion are in effect unfalsifiable claims similar to saying that a tiny, undetectable teapot exists between Earth and Mars. In his view, the burden of proof lies with those making such claims to show that they are true.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

Bertrand Russell

Russell lived in the modernist period (from the Enlightenment to the first part of the twentieth century) when most scientists believed that the nature of our world is in the realm of scientific proof. Although it is surely true that we can “objectively” assert certain things about the empirically accessible part of our world (see part 2 - the link is at the bottom of this essay), we know today that there are large parts of the cosmos for which this is just not possible (scientists nowadays think that more than 93 % of our world may be “dark” to our instruments). Even the well-known theories of general relativity and quantum physics describe events and entities that are not empirically accessible. The “Big Bang” is not so accessible; quantum entities (particles) are also outside direct empirical access – they are mathematically described as existing in a complex (abstract) space which is definitely not our space! In Quantum Field Theory they are even described as being outside proper space-time. Only when we measure them do they appear in our space-time.

In this world, the idea of “proof” evaporates. That which Russell set out to do in this regard is today generally regarded as a total flop (i.e. his "logical atomism" which engendered the discredited "logical positivism"). Instead, we find that various “interpretations” of especially quantum physics theory have been developed – all of which view the reality of our world very different (for example, the Copenhagen interpretation, Bohm's interpretation, Von Neumann's observer interpretation and the many-worlds interpretation). Today we speak in the philosophy of science of the metaphysics of quantum physics. That is, there are various metaphysical views as to how the world really is beyond our empirical access thereof. In the place of “proof”, we are now engaged with “interpretations” due to the simple fact that we as humans are severely constrained in our experiential and experimental access to the world (see part 2).

This problem has been foreseen long ago by Kant. A large part of his philosophy is concerned with the constrained nature of our human sensibility and understanding which in turn restrict our ability to acquire “objective” knowledge. Once we proceed in our thinking and theoretical (mathematical) modelling beyond these boundaries, we cannot obtain proof of anything. We may have good reason to think that something is such or such but one cannot prove it. Even in the case of our best scientific theories, nothing is proven!

Although we may have indirect evidence which confirms the “correctness” of our theories, this can never prove that the world is like that. In the “Big Bang” theory, for example, we have indirect evidence that confirms this theory: the expanding universe (redshift of light) and the absorption line features in the background radiation which agrees with star formation. Although this is empirically confirmed, the true nature of this event may be very different from what we think – in the same way, that Newton's theory was empirically confirmed but has been surpassed by Einstein's theory [2].

Scientists describe the Big Bang mathematically as a singularity – which merely means that we do not know what really happened. Empirical evidence supports the theory that our material space-time world had a beginning in time. Although there are various speculative mathematical theories about how the Big Bang happened, about all of these confirm that our material space-time world came into being after the Big Bang. Insofar as we engage with the question about what "really" happened at the beginning, this is beyond empirical access. We may have all sorts of speculative ideas about the origin of the cosmos – Christians believe that God created the world – but we can never prove any of that.

This is the bottom line. The time when philosophers thought that only those things that can be proven should be allowed into serious discussion is long gone. We know that the largest part of our world is not empirically accessible and we can always only have theories about that. Now, this is the important point: we can test our best theories to determine if they are empirically confirmed. Although the metaphysics of worldviews goes beyond the metaphysics of science, we can do exactly the same. The metaphysical worldviews of Christians and atheists can be constructed as rational models which may be confirmed or rejected in the progress of science. This is, in fact, the scientific method and there is no other “objective” way to decide between such theories [3]. We can now delineate this approach in more detail.

The metaphysics of worldviews

In this essay, I am primarily concerned with the Christian worldview (insofar as religion is concerned). The most important aspect of Immanuel Kant's work in this regard is that he developed an integrated rational position which is in accordance with the Christian worldview. In opposition to this stood the atheistic worldview which originated in Enlightenment thought. Both these metaphysical views are rationally consistent perspectives and none can as a whole be proven to be true for the simple reason that they are concerned with at least some entities that lay (or do not lay) beyond our experience and experiments. This does not mean that aspects of these metaphysical worldviews cannot over the course of time become accessible to scientific research. In fact, certain aspects did come within scientific range.

Where did the Christian worldview originate? Christians believe that it originated from God's revelation in Scripture. As such they believe that their view is not built upon mere ideas that were taken out of thin air. Rather, it is in accordance with God's revelation of Himself through his Word and his Son to mankind. Although aspects of this worldview are not exclusive to Christians (like the belief in the spirit realm), we focus only on the Christian view in this essay.

Where did the atheistic view originate? The basic point of departure for that view was that there is no God (a-theist). This means that atheists oppose the worldview through which a creator God, souls/spirits, moral law (free choice) etc. become possible. Since all of these stand outside the material cosmos studied by science and cannot on logical grounds in a systematic and consistent way be included in the atheistic view (without leaving at least some space for the idea of God), they were traditionally rejected by atheists. The atheistic view effectively originated from a scientism view which regards empirical science as the basic norm in constructing any metaphysical view of our world.

Immanuel Kant presented the basic aspects of these opposing views in terms of opposing logical possibilities. In the fourth antinomy discussed in his famous Critique of Pure Reason, he sets the possibility of a necessary being (i.e. God) who brings forth contingent existences against the opposing view which rejects that. In the third antinomy in the same work, he sets the possibility of an intelligible cause (a cause that we can merely conceive of intellectually) that produce phenomenal effects against the opposing view which only allow for deterministic causes. The first position is consistent with a creator God who created our material world which came into being at the beginning of our cosmic history. The second position rejects the idea of such a God and thinks that everything always existed in the context of mechanistic causality.

Kant's third antinomy was also important for another reason. It is not merely consistent with a first beginning of our universe; it also makes free choice possible. Without such absolute spontaneity – that is, when only deterministic causes exist – there cannot be any free choice. This means that God's requirement that humans follow the moral law only makes sense if humans have free choice – that is if such spontaneity exists in the cosmos. The traditional atheistic view rejected the possibility of free choice since through that the possibility of the moral law given by God as the requirement for human living is established.

The problem for Kant's view was that such spontaneity is not logically possible in a mechanistic (that is, material) world. A world that consists only of matter that is connected mechanistically through deterministic causality can in no possible way supports absolute spontaneity. The only solution for Kant was to postulate the existence of another realm which is not in space and time and therefore not sensibly accessible in experience and experiment. Since this realm is not sensibly accessible, we as humans can only think about the existence of such a realm – which is why Kant called it the “noumenal realm”, derived from the Greek word for the mind (“nous”). The logical possibility of absolute spontaneity and human choice only arises when we postulate the existence of such a realm.

This realm also makes it possible that non-extended wholes-and-parts (situated in this noumenal or supersensible realm as it is also called) may have a spontaneous potentiality to produce extended parts and aggregated wholes in the context of nature. This means that everything in nature is not necessarily produced through mechanistic causality! The first view excludes "creation" insofar as it is a random process; the second view is consistent with a creator God who included an unfolding design in the cosmos when he created it [4]. Kant presents these two opposing possibilities as part of his philosophy of science in the seventh antinomy in the Critique of the Power of Judgement.

The interesting thing about the noumenal realm is that it was already introduced in philosophical conversation by the Greek philosopher Plato. Kant's contribution was to ascribe “freedom” to this realm. For human freedom (choice) to be possible, such a realm should not only exist; a part of humans should also be situated in that realm. Kant calls that the soul. If humans have souls – that is, noumenal selves – then they may be able to choose between good and evil in accordance with God's moral laws. In this way, the possibility of a creator God, of human freedom, of the soul and of the “noumenal realm” (the realm of the soul/spirit) are introduced as part of a consistent rational conception of the world. This is consistent with the Christian worldview and Kant effectively contrasted it with the prevailing atheistic view of that time which postulated exactly the opposite.

Over the next century, the Kantian metaphysics was rejected by philosophers and scientists alike. In the modernist period atheists strongly believed that there is no God, that our material universe had no beginning, that absolute spontaneity does not exist, that humans have the mere illusion that they have free choice, that no supersensible realm exists and that there can, therefore, be no part of humans belonging to that realm (souls/spirits). The whole march of freedom on the political sphere which started with the French Revolution was seemingly merely one great collective illusion! (That is if we take the atheists really serious).

Scientific progress

We all know that the world has changed a lot since the time of Kant. We can now go back to our million dollar question: which worldview has been consistently confirmed through science as correct insofar as that is possible to do that? Was that the Christian worldview or the atheistic one? One need not be a scientist or philosopher to see what has happened over the course of the last two centuries. Most of the things that Kant postulated have been accepted as part of our scientific worldview! And most of those things that atheists believed in were rejected by science – although I must admit that there are some who are still trying (struggling) to keep the pure deterministic worldview alive!

The first thing regarding the Christian worldview in which Kant was right insofar as it is widely accepted by the scientific community today, is that our material world had a beginning. The scientific model which confirms that is the Big Bang model. Although there was originally an enormous amount of resistance from atheists within the scientific community against this theory due to its obvious metaphysical implications (which seems to be largely forgotten nowadays!), science has accepted it as part of its own.

The second thing in which Kant was right, is that non-determinism (which we may understand as absolute spontaneity) has been empirically confirmed in science where we see its most dramatic confirmation is in the form of atomic decay - which atom will decay, or when, is completely indeterminate. Niels Bohr used the empirical evidence for quantum spontaneity to formulate his quantum postulate. This does not mean that some (atheistic) quantum theorists have not tried (and are still struggling) to present consistent interpretations of quantum theory that are merely deterministic. The problem is that, as Michael Redhead has shown, when the Aspect experiment confirmed the violation of the Bell inequality, it at the same time proved that all forms of determinism had broken down [5]. I think one can safely accept that most scientists today believe that indeterminism is a fact of our universe.

The third thing in which Kant was correct is that there is another non-material part of our universe which exists within the context of our world - that is, Kant's "noumenal" or "supersensible" realm. Although Kant thought that this realm may never become empirically accessible, the decoupling of space and time in quantum mechanics has allowed scientists to at least indirectly confirm the existence of such a realm which is nowadays called the quantum realm (see part 1). Not only is the quantum realm indeed outside our space-time as Kant postulated, it also behaves in a manner that is totally different from our classical world as described by all mechanistic theories (like general relativity). And it is exactly in the context of this realm that indeterminism/spontaneity is observed - exactly as Kant proposed.

What we find is that the basic features of the Kantian rational position that agrees with the Christian worldview have been accepted in science. On all these points the Christian worldview may be regarded as correct whereas the atheistic view held by the pioneers of that position is generally rejected. I would even go further than this. I would suggest that even the one great showpiece of atheism, namely the neo-Darwinian theory of evolution which is a purely mechanistic theory, is under threat in this regard. Some leaders in the new academic discipline of quantum biology have recently proposed that even genetic mutation may be due to non-mechanistic factors [6]. The incorporation of quantum mechanics in biology immediately implies a role for indeterminism/spontaneity and the kind of design that Kant postulated [4].

This is not the only remaining atheistic pillar of faith that is challenged by contemporary science. In the theoretical reconstructions regarding "dark" matter, we find that scientists propose that such matter is not confined to the high end of the energy spectrum - they now accept that there may be dark entities (like atoms etc.) that occupy even our human bodies [7]. This means that humans may have a dark "body" which corresponds with their fleshly body. In this regard, it seems to me that even the existence of the Kantian soul which exists as a noumenal self may in time be scientifically confirmed!

A new argument for the existence of God

How did atheists react to the rejection of their traditional position? Some merely adapted and took the scientific position as their own - even though it does not fit consistently into one comprehensive rational atheistic position. Others have adopted theoretical positions that are consistent with the atheistic view - for example, certain speculative theoretical interpretations about how the Big Bang happened which exclude the possibility of a creator God. These atheists are indeed able to save their position - but their solution cannot be confirmed or denied (i.e. that this was what happened) since it is beyond empirical reach!

Now, Christians also cannot prove that God created the cosmos for the same reason. As such it is of no use to argue about things that lay beyond empirical confirmation. We should rather stay within the confines of the scientific method - we should test the metaphysical positions as theories against empirical evidence in the context of the progress of science. When we consider the Christian and atheistic positions in historical context, it is clear that the currently accepted scientific position that the material space-time universe had a beginning in time, is in conflict with the original atheistic position in this regard. Such is the clear evidence that the cosmos includes aspects where determinism breaks down and that the quantum realm is a supersensible realm. If atheists are honest about their worldview within a historical context, they would at least admit that science has been much more in line with the Christian position than the atheistic one!

Atheists often say that they are mere atheists in the sense of not believing in God. As such they then adopt the ever-changing scientism position - often saying that their position is not a metaphysical position at all! They are merely taking the science position! The problem is - as I have already mentioned - that insofar as this approach allows them to make claims that go far beyond the domain of science this is just another metaphysical position. This metaphysical position, however, has certain disadvantages when compared with a fully-developed rationally-coherent atheistic position that can be tested over time. This position is per definition unfalsifiable! It can never be presented as a true metaphysical position that can be subjected to scientific scrutiny - it merely changes its colours with the progress of science. And there are always all sorts of "teapot-in-the-gap" theories available to support their "position". Russell's heirs do not seem to share his concerns in this regard.

Some atheists and agnostics may be described as "soft" in the sense that they are inclined to take that position on other grounds. In some way the popular narratives that are propagated by the mass media which often involve a strong anti-Christian bias appeal to them. These may include the false but popular claims that the Bible is an untrustworthy source of information. I discuss such positions elsewhere for those readers who are open to carefully consider them [8].

Although God's existence cannot be proven, I present a theoretical model (the Kantian model) which takes God's existence as the point of departure. This model is well-delineated with particular predictions and as such it is falsifiable. In modernist times it was believed to be false - but since then three of its basic predictions which have all been considered highly improbable (even impossible) at the time, have been confirmed, namely that our space-time universe had a beginning, the occurrence of indeterminism (absolute spontaneity) in quantum physics and the existence of a supersensible realm (the quantum realm). Two other predictions may be confirmed over the next few decades (an unfolding design in the cosmos and the existence of the human soul). On no single point have this metaphysical position been shown to be wrong!

We can compare this theoretical (metaphysics) model with the Big Bang model. Although the Big Bang model is a mathematical model and the Kantian metaphysical model a mere rational model, both make clear testable predictions. In the same manner that the singularity of the Big Bang is forever outside empirical reach, God is forever outside such reach. In the same way that scientists accept the empirical evidence for the (unprovable) Big Bang as a good reason to think that it happened, we may accept the empirical evidence for God's existence. I can see no substantial difference between the two approaches.

In the final instance, it is, in fact, amazing that the Christian worldview was arrived at not via science but through divine revelation! This means that insofar as metaphysical truth is concerned – that is, which concerns the totality of our human existence – divine revelation is a better guide than science when tested with the only “objective” scientific measure available to us as humans, namely the scientific method.

Conclusion

We are long past the point where philosophers think in terms of "proof" when it comes to metaphysical issues. Only those who are uninformed would today take such positions. Our world is just too complex for that. What we have instead are various metaphysical positions which may be tested in the framework of the progress of science to see whether they have withstood the test of time. I am afraid that we must concur that the atheistic position has been a total failure in this regard. When we take it as a theory that is submitted to empirical testing, it has been spectacularly unsuccessful.

So, why are atheists unmoved by this? One reason is that their position has been constantly shifting - just like a chameleon. The new generation is not aware that the current scientific position is much more in line with the Christian worldview - and I predict that this trend of confirming the Christian position will continue in future - than the atheistic one from two hundred years ago. Since such historical considerations are about the only "objective" way in which we can test such metaphysical views, I recommend that atheists reconsider their "teapot-in-the-gap" approach of always calling upon unfalsifiable theories to counter the Christian position and accept that science has not been on their side in this conversation.

In contrast, I presented a new argument for the existence of God which shows close agreement with the scientific approach through which the Big Bang is accepted. Not only is the Kantian model falsifiable, it has in fact been confirmed - insofar as it has become possible - against great odds in the progress of science. If one believes in the Big Bang, one should seriously consider believing in God too.

[1] There are Christian viewpoints which do not accept the idea of free will. Our concern is not here which such theological issues.

[2] We may say that a theory is "empirically confirmed" insofar as we are able to confirm its predictions within the scope of empirical science. But that does not mean that we know what the world is "really" like! Aspects of the theory might be forever outside empirical reach. As such we may compliment "empirically confirmed" with "good reason to think".

[3] The scientific method is “objective” insofar as it enables us to test whether theories are empirically confirmed in the framework of certain parameters.

[4] I plan to discuss this in more detail in this series

For a technical discussion see Mc Loud, W. 2015. Introducing a Kantian Interpretation of Quantum Physics, in accordance with Kant's Philosophy of Science in the Critique of the Power of Judgment, reinterpreted and reworked with special attention to the supersensible realm. Masters thesis. UCT. Cape Town.

Also by W Mc Loud: Kant, Noumena and Quantum Physics published in Contemporary Studies in Kantian Philosophy 3 (2018)

[5] Redhead, M. 1987. Incompleteness, Nonlocality, and Realism. A prolegomenon to the philosophy of quantum mechanics. Oxford: Clarendon

[6] Al-Khalili, J & McFadden, J. 2014. Life on the Edge, The Coming of Age of Quantum Biology. London: Bantam Press.

[7] See, for example, http://www.space.com/21508-dark-matter-atoms-disks.html.

[8] Can we still believe the Bible? A hermeneutical perspective

Can we still believe the Bible? An archaeological perspective

Can we still believe the Bible? A scientific perspective

Can we still believe the Bible? A prophetic perspective

Die probleem met Goddelike wreedheid in die Ou Testament

Author: Dr Willie Mc Loud (Ref. wmcloud.blogspot.com)

The author is a scientist-philosopher (PhD in Physics, MA in Philosophy) and has written a book on the Sumerian roots of the Bible (Abraham en sy God (Griffel, 2012)). He writes on issues of religion, philosophy, science and eschatology.

Science and God. Part 1: The problem of spontaneity in quantum mechanics

Science and God. Part 2: Science and our restricted human understanding

Science and God. Part 4: Science and the spiritual realm

Science and God, Part 5: In defense of the soul

Science and God. Part 6: Science and Atheism

Science and God. Part 7: Science and spiritual intuition

Science and God. Part 8: The Christian and Evolution

Readers are welcome to forward this essay to their atheist, agnostic and Christian friends

Dr McLoud, if I understand correctly, the deterministic part of the universe ("nature") is deterministic to the point where randomness is not possible or allowed, since any true randomness would be the result of a noumenal input having a result in the "natural" world? Things like atomic decay is considered a random (although statistically describable) process in modern physics (please correct me if I am wrong). Is there not reason to believe that true randomness cannot be part of "nature", could randomness possibly be a true property of "nature" rather than ascribing it to a noumenal realm?

ReplyDeleteSorry, I meant to say : "Is there not reason to believe that true randomness CAN be part of "nature"...

DeleteThere are various kinds of randomness. Some kinds are in line with determinism - we are just not able to calculate all the lines of input (in a heated gas). Then there are the kind which is in line with spontaneity - which is found in the quantum realm (atomic decay). So, determinism (and the randomness going with it) belongs to the "classical" picture of the world whereas spontaneity (and the kind of randomness consistent with that) belongs to the quantum (noumenal) realm. Redhead (see note 5) has shown that quantum randomness (at least insofar as the Bell theorem is concerned) is non-deterministic.

ReplyDelete